| JOURNALISM | MISC | ABOUT | CONTACT | LINKS |

| Media: RFI, 17-10-17 | • | Calendar | • | Topics | • | • | ← | • | → |

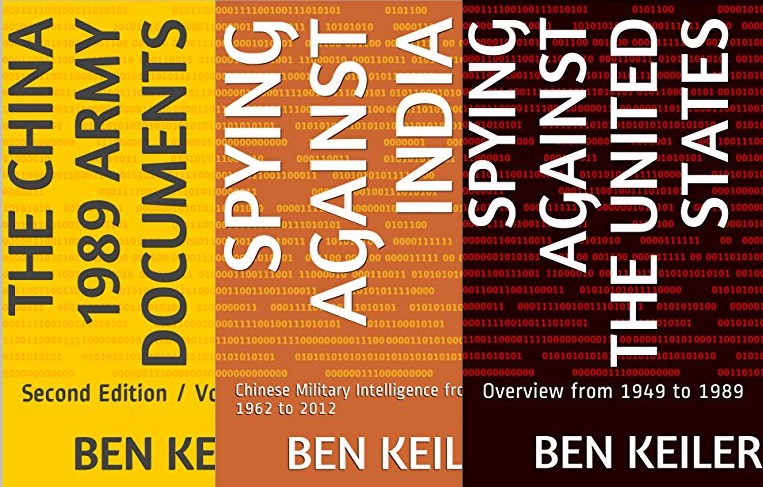

In the vaults of Amazon.com’s self publishing market place, a growing series of books exposing China’s

dark secrets is seeing the light. Six books with colorful covers, which constitute the “China Secrets”

series, introduce a reader to the fascinating world of China’s internal – or neibu – documents. But many

questions remain.

In the vaults of Amazon.com’s self publishing market place, a growing series of books exposing China’s

dark secrets is seeing the light. Six books with colorful covers, which constitute the “China Secrets”

series, introduce a reader to the fascinating world of China’s internal – or neibu – documents. But many

questions remain.

Jan van der Made

Since 2015, unnoticed by the large majority of the China watchers, the books, with titles like The China 1989 Army Documents, Spying against the United States, Spying against India and others can now be bought on Amazon.

Author Ben Keiler [probably a pseudonym] claims the documents are being put before the public “for the first time ever”. They shed a new and unique light on events as diverse as the 1989 Tian’anmen Square massacre and the martial law imposed in Tibet three months before, the China-India border conflict culminating in hostilities in Bhutan earlier this year

It also offers detailed descriptions of the state of Chinese army intelligence gathering in respect of the US, South Korea, Japan and other countries, since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Real or not?

In total some 500 pages, filled with copies of documents, military maps and tables have been published. The big question is: are the documents real? For centuries, sinologists have struggled with the question of authentification of documents. Andrew Nathan and Perry Link published the Tiananmen Papers in 2001, a book with translated secret documents leaked or provided by “Zhang Liang,” a pseudonym, that minutely describe the policy process that lead to the Tian’anmen crackdown on June 4, 1989 in Beijing. They said in the preface that the documents went through a meticulous five-stage process of selection before publication was decided, and they still cannot confirm their veracity completely.

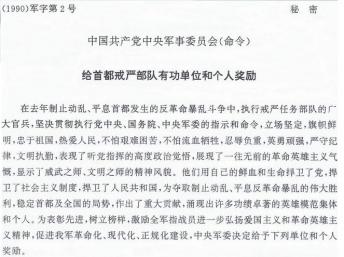

Keiler criticizes the lack of access to the original documents in the Tiananmen Papers, saying that they “contain not a single copy of an original [ ] and this fact makes it easy to challenge the content.” Indeed, Keiler’s 1989 Army documents do show copies of maps and documents that list in minute detail the of the People’s Liberation Army [PLA]’s troops before and during the attack on Tian’anmen Square on June 4, 1989. The square had been occupied for weeks by students demanding an end to corruption, more transparency and a chance to participate in the politcal process. China's leaders had imposed martial law, and moved the army against Beijing's demonstrating civilians.

There is a minute-to-minute army account of how PLA troops fight themselves through the crowds reaching

the square and removing the remaining students by 04:00 am, as planned. In a preceding chapter of the book,

Keiler illustrates - again showing highly classified neibu material - how the PLA crackdown in Tibet,

in March 1989, served as an example for the Tian’anmen attack. The author reproduces PLA policy documents

and lists of material, including guns and vehicles used, down to the amount of bullets handed out to the

martial law troops who were to control the Tibetan protesters.

There is a minute-to-minute army account of how PLA troops fight themselves through the crowds reaching

the square and removing the remaining students by 04:00 am, as planned. In a preceding chapter of the book,

Keiler illustrates - again showing highly classified neibu material - how the PLA crackdown in Tibet,

in March 1989, served as an example for the Tian’anmen attack. The author reproduces PLA policy documents

and lists of material, including guns and vehicles used, down to the amount of bullets handed out to the

martial law troops who were to control the Tibetan protesters.

Who is Ben Keiler?

None of the Chinawatchers contacted by RFI was familiar with Ben Keiler or his work, but some expressed doubts: “If the documents were authentic, major publishers would have been interested, and the Chinese Government would have reacted strongly against Amazon. So far I have not seen a prima facie case to do this,” says Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at the School for Oriental and African Studies [SOAS] in London.

Perry Link, one of the two editors of the Tian’anmen Papers says that “one needs to be skeptical of these things, and yet it would be a mistake to reject them out-of-hand,” while Nathan insists that the documents can’t be authenticated “just by looking at them. It requires a lot of research,” he says.

Others were more forthcoming. Michael Dillon, founder of the Center for Contemporary Chinese Studies at the University of Durham and author of Deng Xiaoping, the Man who Made Modern China, said, after “a preliminary look,” that he found the “level of detail [of the 1989 Army Documents] is convincing,” but admitted that it was not possible to be certain if they were originals. He also pointed out that the lack of the significant red stamps and handwritten autographs of relevant leaders on some of the documents presented could mean they are just a draft or print out. "[They]cast doubt on when and how they were issued and used. Even if they are genuine we cannot be sure that they were final drafts,” he says.

But Song Yongyi, librarian with California State University, who himself did extensive work exposing

cannibalism during the Cultural Revolution in the Guangxi Autonomous Region, going through

massive amounts of secret documents

, said that one set of documents about the Korean War looked very familiar to him.

“When I was collecting documents about PRC history, I did see some of them. They are government

publications [on] internal and classified level,” he writes in an email to RFI. Other volumes of the

“China Secrets” series dig deep into Chinese intelligence sources, showing the detailed level of

knowledge Beijing had of military positions of the Indian army during the 1962 border war, South Korean

positions during the 1950-53 Korea war; always with many illustrations of colorful maps and [parts of]

documents and extensive commentary.

But Song Yongyi, librarian with California State University, who himself did extensive work exposing

cannibalism during the Cultural Revolution in the Guangxi Autonomous Region, going through

massive amounts of secret documents

, said that one set of documents about the Korean War looked very familiar to him.

“When I was collecting documents about PRC history, I did see some of them. They are government

publications [on] internal and classified level,” he writes in an email to RFI. Other volumes of the

“China Secrets” series dig deep into Chinese intelligence sources, showing the detailed level of

knowledge Beijing had of military positions of the Indian army during the 1962 border war, South Korean

positions during the 1950-53 Korea war; always with many illustrations of colorful maps and [parts of]

documents and extensive commentary.

What does Keiler want?

The identity of the author, as well the way he obtained the documents is shrouded in mystery. “Questions regarding who’s behind the China Secrets Series are secret and will not be answered,” he says in the preface. “Years of efforts and movements of persons went into the effort to make it as difficult as possible to hide the methods and all the persons involved” in obtaining the documents. The reason: under China’s stringent security laws and regulations, leakers of “state secrets” may face the death penalty.

But Keiler explains why the risk may be taken: in the preface of the China 1989 Army Documents, he says that by exposing details about army units involved in the crackdown, “people responsible can be named and if possible persecuted ... once places, units and names are known and officers can no more hide behind a screen of [a] 'state secret' it will become more difficult to find persons ready to use machine guns against civilians the next time such an incident happens in China.”

Publication of Chinese intelligence on the US, India, South Korea and other countries would give researchers and, ultimately, politicians, a better insight in how the Chinese military acts under extreme circumstances.

Meanwhile, production goes on. In 2017 some six volumes were produced, and 11 more are on the way. Among the new books will be the first publication of top secret documents on decoding, China’s 1979 war with Vietnam, a history on Chinese army mapping and a book on the Tibetan uprising in 1959 and the Chinese crackdown. Until now, the Chinese government has offered no reaction regarding the leaks.